With Pencils Poised

A simple request from an overseas broadcaster took me down the path of researching with Trove. When the hosts of Palabras Dibujadas (Drawn Words) – a weekly Argentinian radio program devoted to shorthand – asked me to write an article for their program on Australia’s history of shorthand, I thought this would be an easy task. Surprisingly, I could find no comprehensive Australian history on shorthand – a written language that had provided so much to the parliamentary, legal, business, and social fabric of our society. I immediately set out to amend this situation.

Trove was an invaluable resource when researching for my book, With Pencils Poised… A History of Shorthand in Australia. Society is generally aware of the visible aspects of shorthand through Hansard, court stenographers and business stenography. Trove, however, provided me with the stories and the newspaper commentary, equivalent to today’s social media, which provided animation for my narrative.

Shorthand competitions

To a shorthand writer, this skill is so much more than an employment ticket. It is an art and even a sport. Judges’ detailed notes from keenly contested events like the annual Shorthand Championship of Western Australia were published in the press. Usually, comments were encouraging and complimentary, but there was no guarantee, as readers came to realise in 1933. Without holding back, the examiners reported there were no successes in either of the two higher sections. A newspaper article in The West Australian, reported that ‘the standard of work is very poor indeed, and it is impossible to comment at any length on the character of the work submitted.’

The Board of Education defended candidates by outlining the challenging circumstances they experienced. Apparently, it was indeed a dark and stormy night. The storm, accompanied by a boisterous wind, hail and thunder made it difficult to hear. The room was so bitterly cold that writers could hardly hold their pens or pencils. Undeterred, the Championship continued as a successful annual event.

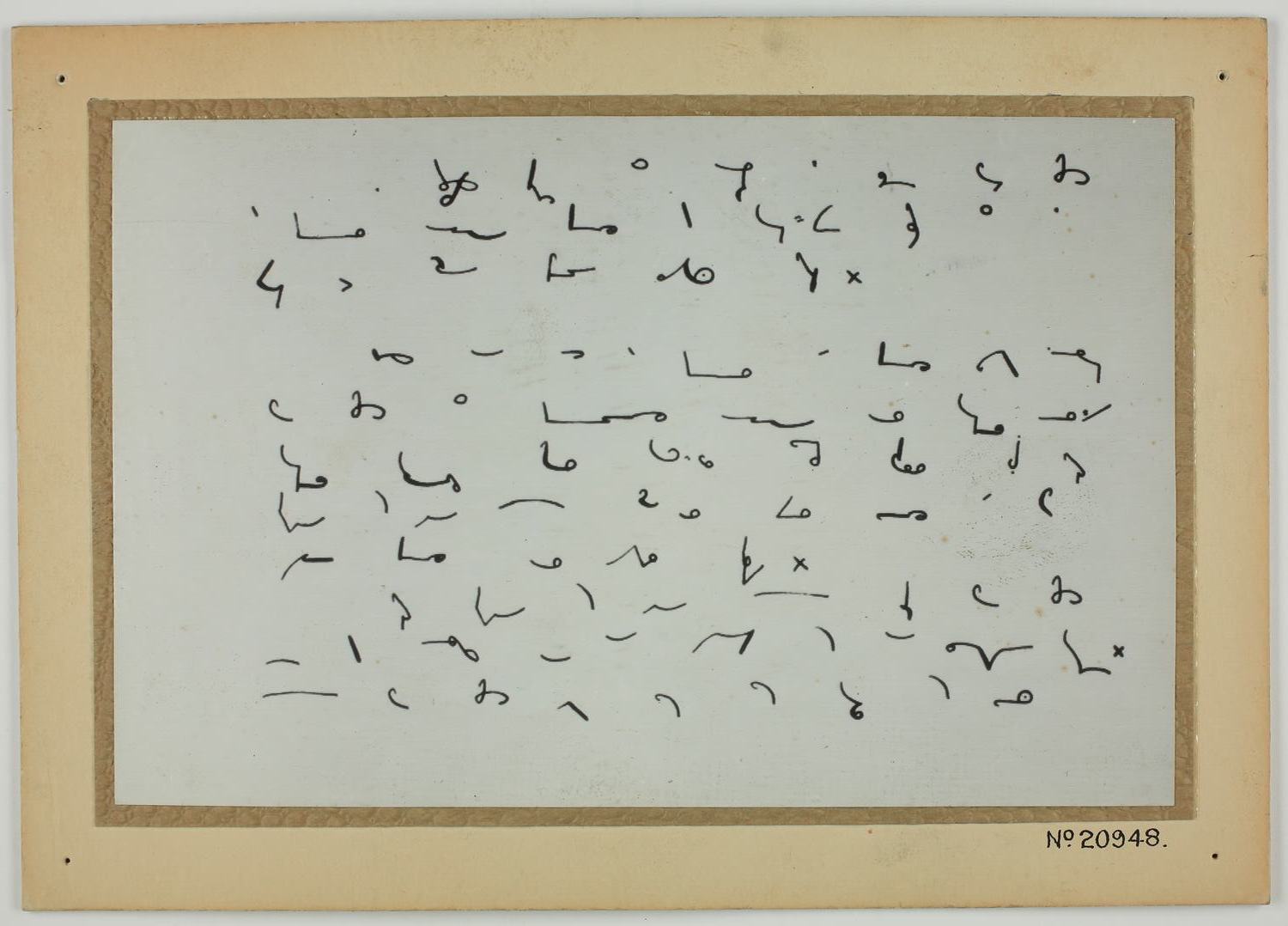

In 1907, a different type of storm erupted due to shorthand. Eisteddfods had gained popularity in Australia since the 1870s. Emulating Welsh competitions, some Australian eisteddfods included shorthand categories. These were not based on speed. Rather judges assessed the quality of penmanship, including accuracy of outlines, taking into account the exacting nature of the skill.

Following the Balmain Eisteddfod in 1907, shorthand featured heavily in the press. Trove revealed that at the time of judging the choral performances, an adjudicator read his notes, referring to an identical error by both the Balmain and Enmore choirs. Balmain lost no points, whilst Enmore did. During the ensuing press uproar, the judge disputed the reporting of his words. It came to light that two shorthand writers in the audience independently recorded his judgement. The judge’s explanation was that they both took it down incorrectly.

‘Sir – In reply to your paragraph in yesterday’s “Herald” relative to letters from defeated choir members at the late Balmain Eisteddfod, I now say that the alleged shorthand reports taken by the defeated members are entirely wrong. These reporters (no doubt owing to over-anxiety) have evidently messed up the numbers of the various choirs, or else have misunderstood me.’

Rage was maintained with letters from “Front Seat” and “Lady Member” all attesting to the shorthand writers’ reports. The results remained unchanged, however, with the aid of shorthand writers, the Balmain community were united in their support for their Choir.

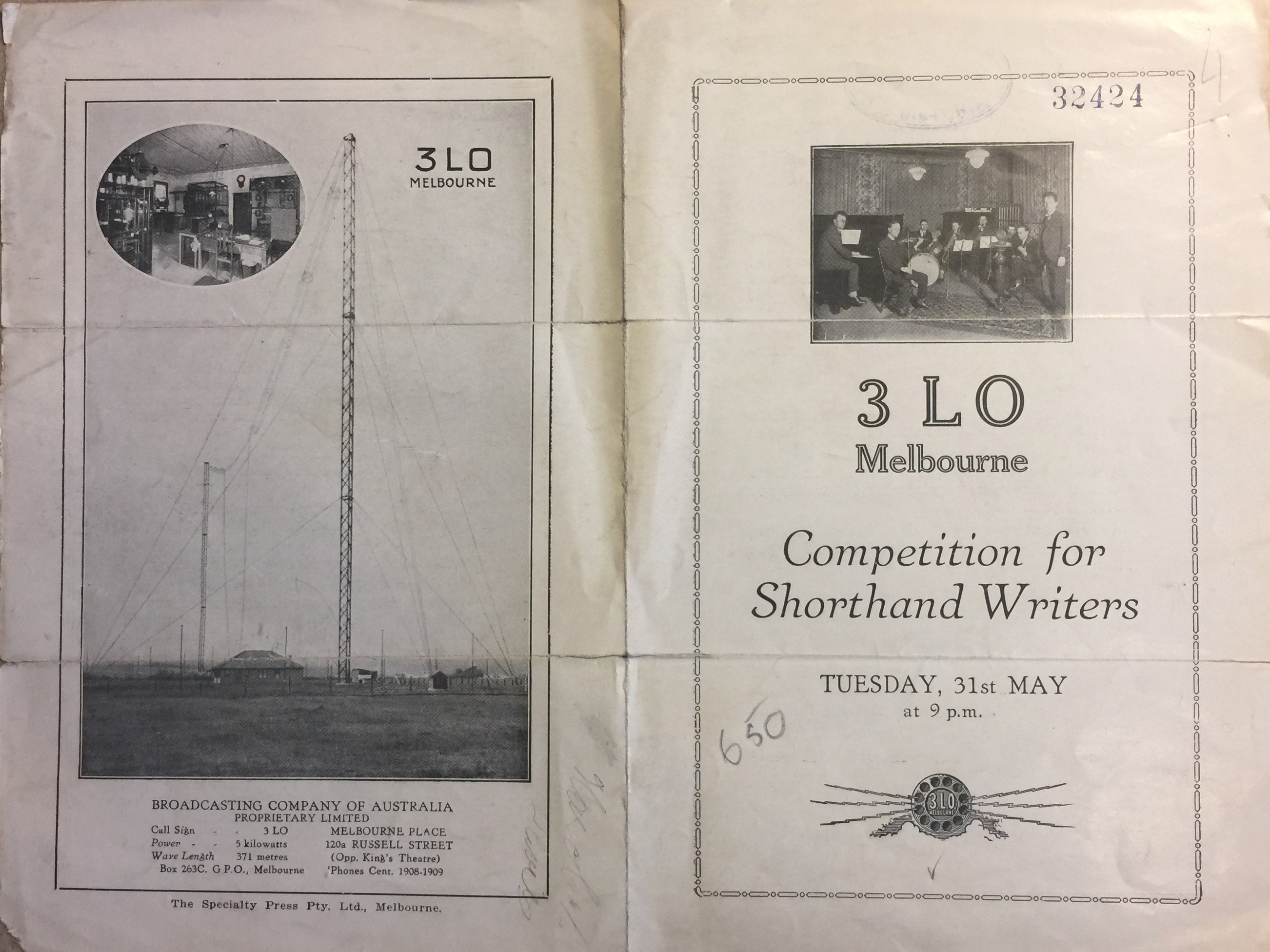

Over the wireless

The introduction of the wireless provided shorthand writers with opportunities in their own homes. In 1927 The Wireless Weekly announced the first shorthand writing competition, hosted by Melbourne radio station, 3LO. Inviting residents in Australia and New Zealand, competitors had to take dictation from the wireless, then post their notes and transcription to the station. Thousands of entries were received.

As 3LO rated their competition as prestigious, the organisers saw no need for a monetary reward for the winners. Successful shorthand writers received a medallion and accompanying accolades.

Shorthand provided opportunities for communities which otherwise would be disadvantaged. In 1931, Western Australians tuned into their wirelesses for the radio serial, The Hair, by A F Alan. Although intended as listening entertainment, the use of shorthand multiplied circulation of the play. A wireless radio was out of reach for many families during The Depression. With a shorthand writer sitting near the wireless, episodes of The Hair were recorded verbatim each week, for publication in the local newspapers. A newspaper could be passed around between families and provided entertainment and anticipation for the next episode.

Meanwhile, a similar activity occurred in remote areas of Queensland. The Queenslander, a bi-weekly radio news service from 4QG, was not always accessible to those without a wireless or people who were working during the broadcast. A local shorthand writer recorded the news, typed it with several carbon copies and distributed them within the communities. In areas where transmission was limited a reverse method was employed. The shorthand writer would listen to the news report on shortwave radio, then relay it – from his shorthand – on his local station.

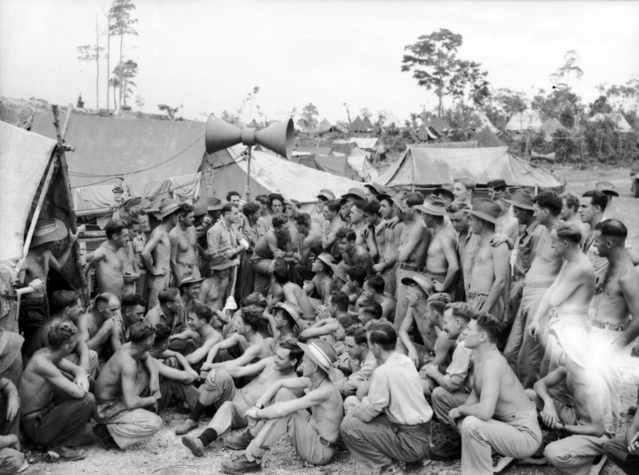

In 1944, Australian RAAF personnel stationed in Dutch New Guinea weren’t excluded from the Melbourne Cup. A shorthand recording of the race was taken from the ABC’s broadcast then relayed ‘stride by stride’ over amplifiers for the camp to hear. The Argus reported that Corporal R L Stokes of Williamstown, a former race owner, acted as broadcaster.

All these anecdotes, stories and historical material might well have been lost forever if it had not been for the resources so valuably archived in Trove.

Carmel Taylor is the author of With Pencils Poised... A History of Shorthand in Australia and the creator of a Shorthand History Walk in Melbourne’s CBD. She has held a fascination for shorthand since the age of 12, when she was gifted a 1915 Pitman Shorthand book. She is also a shorthand teacher, collector of antiquarian shorthand books and has worked as stenographer.