Australian Ocean Histories and the Magic of Trove

When the Trove team at the National Library of Australia wrote to ask if I ever used Trove during my research, I was a little taken aback. They had seen an essay I had written on the sharks of Sydney Harbour, and in it were references to Australian newspaper articles and newspaper illustrations. They wondered if Trove was involved.

The truth is, I cannot easily remember life without Trove, and moreover, I would be lost without it. Trove has changed my thinking, refocused my interests on the history of media, and given me insight to people and events of the past. For instance, I’ve been researching ocean histories for quite some time, driven by concern for an ecology in peril from climate change. Trove has given me stories of public value, stories around which my last two books have been based: one on early underwater photography at tropical coral reefs including the Great Barrier of Australia and the reefs of the Bahamas (Coral Empire, 2019); the other on the underwater of Sydney Harbour, a book almost entirely based on newspaper stories about perceptions of the under-harbour brought back from the deep by early divers wearing brass helmets and heavy boots (not published yet).

When did I first learn about Trove? I was sitting in the Reading Room at the National Library of Australia (NLA) in Canberra. I was an Honorary Harold White Fellow, and it was 2014. I was researching a project on the Great Barrier Reef and the Australian explorer, Frank Hurley (Figure 1). A librarian in the Reading Room asked if I knew about Trove. To be honest, I didn’t know much.

Newspapers have been an important primary source for my research, but I found the process of accessing them laborious. I’ve never been able to master Microfilm; the spools of film are so tricky to manoeuvre. And long gone are the days when it was common to leaf through bound volumes of original newspapers with a magnifying glass to enhance tiny print.

Sitting in the Reading Room of the NLA, I already had some experience with digitised newspapers. In 2012 I had discovered an amazing article in the New York Times while sitting in the State Library of New South Wales. Without being too dramatic, my discovery that day changed many people’s awareness of the relationship of modern art, particularly Surrealism, with the history of oceans and the undersea. You can read about this in Coral Empire, and it is mentioned in other sources including Margaret Cohen’s new book, The Underwater Eye (2022).

To get back to the point. By 2014, digitised newspapers had already made my research and writing more creative, and more impactful. But I didn’t know much about Trove. In the Reading Room of the NLA I received a short lesson on how to use Trove, and the world of research changed once again.

Within seconds of using the right key words, I had access to articles going back a hundred years. They led me into the distant past, and a history both strange and exciting. They told me how people in 1920 perceived the Great Barrier Reef, what their attitudes were to oceans and the undersea. And then, something miraculous happened.

As I sat at my desk in the NLA, a Sun newspaper article written by Hurley and dated 1926 appeared on my computer screen (Figure 2). There, in the first paragraph, was evidence I was searching for to prove a hunch. It was an important hunch about Frank Hurley’s connection with a famous American photographer, John Ernest Williamson. It was the kind of evidence that a researcher always seeks because it resolves untidy loose ends, and it also shines new light on old subjects. It was a discovery that meant I could give the public a new perspective on Frank Hurley. And I found it in minutes rather than months.

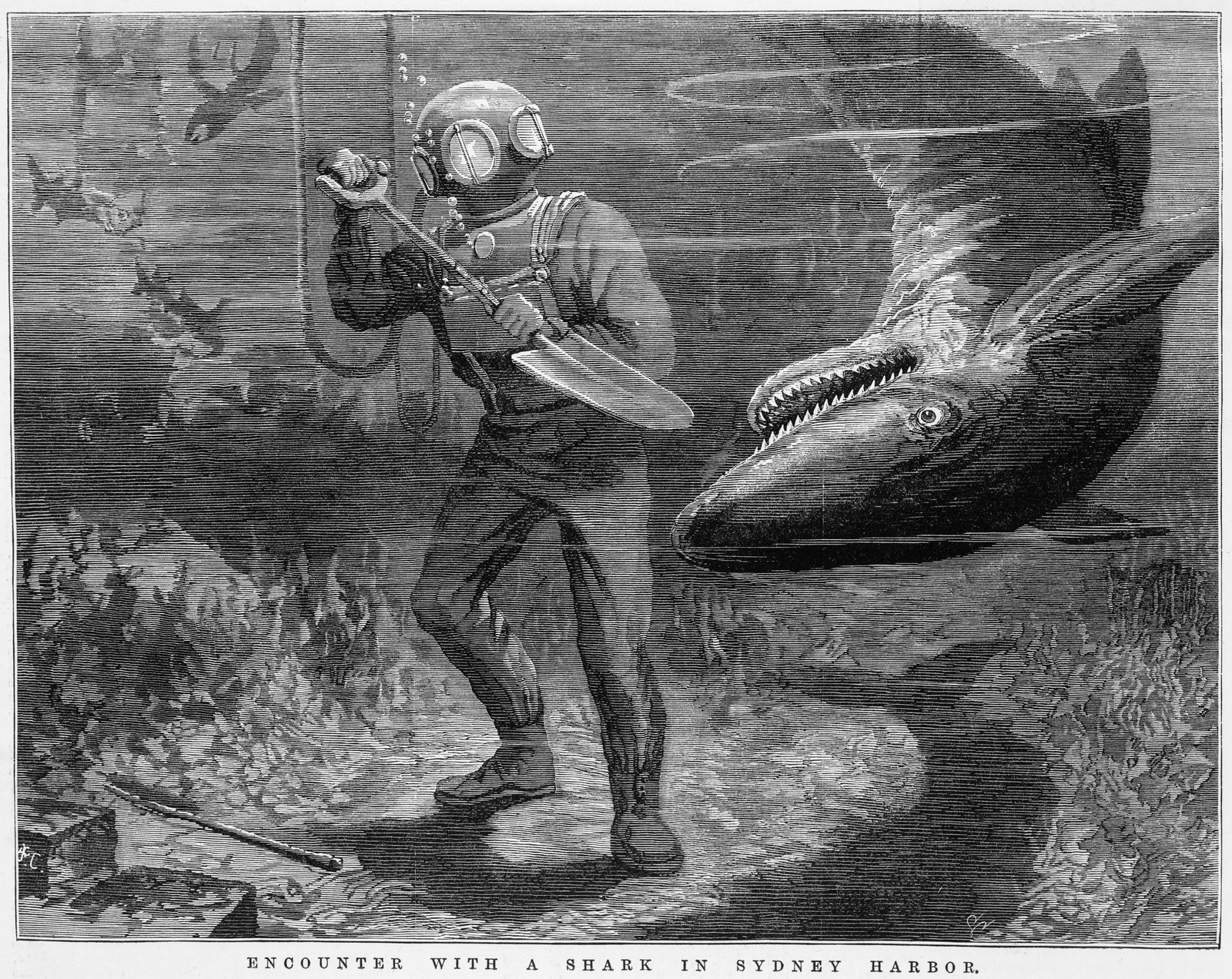

As for the sharks of Sydney Harbour: the article I wrote that the Trove team were interested in was published in 2020 and is based entirely on colonial newspapers that I accessed through Trove. They reveal much about public attitudes in the past towards the sharks of Sydney Harbour, especially a common desire among citizens to exterminate sharks in a society that did not understand the shark’s place in the ecological balance of the sea. On April 15th, 1886, the Illustrated Sydney News published an article with an engraving of a shark hunting scene on Sydney Harbour. The slaughter was described as ‘the most remarkable battle with sharks that has ever been recorded in connection with these waters’ (Figure 3).

But you could say my article is not just about sharks and shark-hating, but also about Trove. Trove as a tool in the process of research that enables the world of the past to come to light quickly, at home, in a café, or anywhere on the planet, illuminating cultural heritage, and enabling richer, more detailed pictures of the past to emerge.