From the front line

Unlike their male colleagues, female journalists in the early days of Australian journalism (and around the world), had to fight tooth and nail for the opportunity to write. Usually constricted to the ‘women’ or ‘society’ pages, female journalists were often underfunded and underpaid. To add salt to the wound, they were often also denied a proper by-line, if given one at all. Instead, their ‘gossip’ was published under pseudonyms or anonymous titles like ‘our lady correspondent.’

Despite the odds stacked against them, then and now, many female journalists have stood up against a patriarchal system that should have never existed.

As Amy Remeikis puts it in her introduction to Bold Types,

“[W]omen have always been a crucial part of journalism. ‘Anonymous’ may have been a woman, but there were many others watching history unfold under a by-line, analysing and explaining it through their own lenses – all while hearing how they couldn't possible understand the significance of the events they were both witnessing and living.”

An unusual life, an extraordinary talent

For a woman of her time, Edith Dickenson lived an extraordinary and unusual life. She was an accomplished journalist and author, photographer, and amateur ornithologist.

‘Wherever she lived or travelled she had with her a pen, a camera, a gun and an eye for the birds she was intent on collecting for science. Sometimes she had her children with her. By the standards of the day, her life was extremely unconventional’.

Born on 30 May 1851, Edith Charlottle Musgrave Bonham spent her early life in Suffolk, England. At the age of 19, she married Reverend William W. Belcher. They had four children together. Leaving her husband and following her lover, Dr Augustus Dickenson, Edith arrived in Melbourne from England in February 1886. This dramatic change in her life’s trajectory is where her story really begins.

Edith’s first-known newspaper appearance was on 30 October 1897 in the Adelaide Observer in a letter titled ‘The wreck of the Phasis. Experiences of an apprentice.’ In it she recounts the experiences of her 16-year-old son, Musgrave, who was an apprentice onboard the British sailing ship Phasis when it ship-wrecked on Lady Charlottle Reef near Labuan.

A year later, regular reports of her travels throughout India, Burma (Myanmar), Singapore and Java (Indonesia) appeared in the Adelaide Advertiser. As ‘an intrepid traveller with remarkable stamina’, Edith’s adventures proved to be popular with the paper’s audience and her travel series was soon published as a book, What I Saw in India and the East. It was this success that led to Edith’s appointment as Australia’s first female war correspondent.

Australia’s first war correspondent

In what has been described as ‘the first media war’, the Boer War, Edith became Australia’s first female war correspondent. Arriving in Durban, South Africa in March 1900, Edith captured the widespread impact of the war as she interviewed families and survivors and visited scenes of both ruin and refuge. Reporting for the Adelaide Advertiser under ‘Mrs E.C.M. Dickenson, Special Correspondent’ or ‘Our Lady Journalist, Mrs Edith C.M. Dickenson, she is praised for her even-handed reporting, documenting the devastation caused by both the British and the Boers.

While her sons trampled through the trenches, Edith followed in their footsteps witnessing and reporting on the trail of destruction left in their wake. She didn’t shy away from the horrors of the war nor was she restricted from it the way her female successors would be in the World Wars to come. After setting the scene with descriptions of the roadside graves of Australian soldiers heralded with Wilfred Owen’s old lie, dulce et decorum est pro patria mori [It is sweet and fitting to die for one's country], Edith recounted a scene that would turn anyone’s stomach: ‘A human head almost fleshless... It was a woman’s body’ (The Advertiser, 9 June 1900).

Later, she would visit, write, and photograph the British concentration camps where women and children, forced from their homes, lived in dangerous squalor-some conditions. When she visited Merebank Camp, she wrote:

‘Refugee Camps’ is a misnomer; they are really prisons... barelegged children paddled through the mud and pools of water, some carrying a load of bread, others a bag of potatoes or a bundle of firewood.’

At Irene Camp, she wrote of the dead and dying. In Bold Types Patricia Clarke writes:

‘She photographed a child of five whose skin hardly covered its bones and was asked to photograph another child because the mother feared it would soon die. By the time Edith reached the tent the child was dead.’

These camps took the lives of over 26,000 Boer women and children. Edith’s lover, Dr Augustus Dickenson, also died while working in one. Edith died a year later, aged 52, on 17 February 1903.

Thousands of words by sea

Despite being one of only three Australian journalists left at the front by mid-1900, cable transmission was deemed too expensive for Edith, a woman, to use. While breaking news from the front was transmitted via almost-instant cable, Edith’s dispatches would arrive six weeks later via sea mail.

While war censorship means we may never know the full extent of what Edith experienced and reported on while in South Africa, her extensive articles in the Advertiser are evidence enough of the many thousands of words she would have handwritten in the field.

In her prologue to Bold Types, Patricia Clarke draws attention to this inequality, while also pointing out an unforeseen benefit:

‘Many of their words remain in print while more ephemeral cable news sent by male correspondents was submerged by subsequent events’.

Find her words, know her name

For well over a century, Edith Dickenson, like many of her female contemporaries, was an obscure footnote in history. Today, we recognise her achievements as a journalist.

You can discover and read articles by Australia’s first women journalists, including Edith, in Trove in our Bold Types collection feature. You can also contribute to help highlight the work of these trail-blazing women by locating and tagging their articles in Trove.

To find articles by Edith Dickenson, search The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA: 1889 – 1931) for:

-

“Mrs E.C.M. Dickenson, Special Correspondent”

-

“Our Lady Journalist, Mrs Edith C.M. Dickenson”

To add her articles to the Bold Types collection feature, add the tags:

-

Bold Types

-

Edith Dickenson

View and contribute to the collection feature

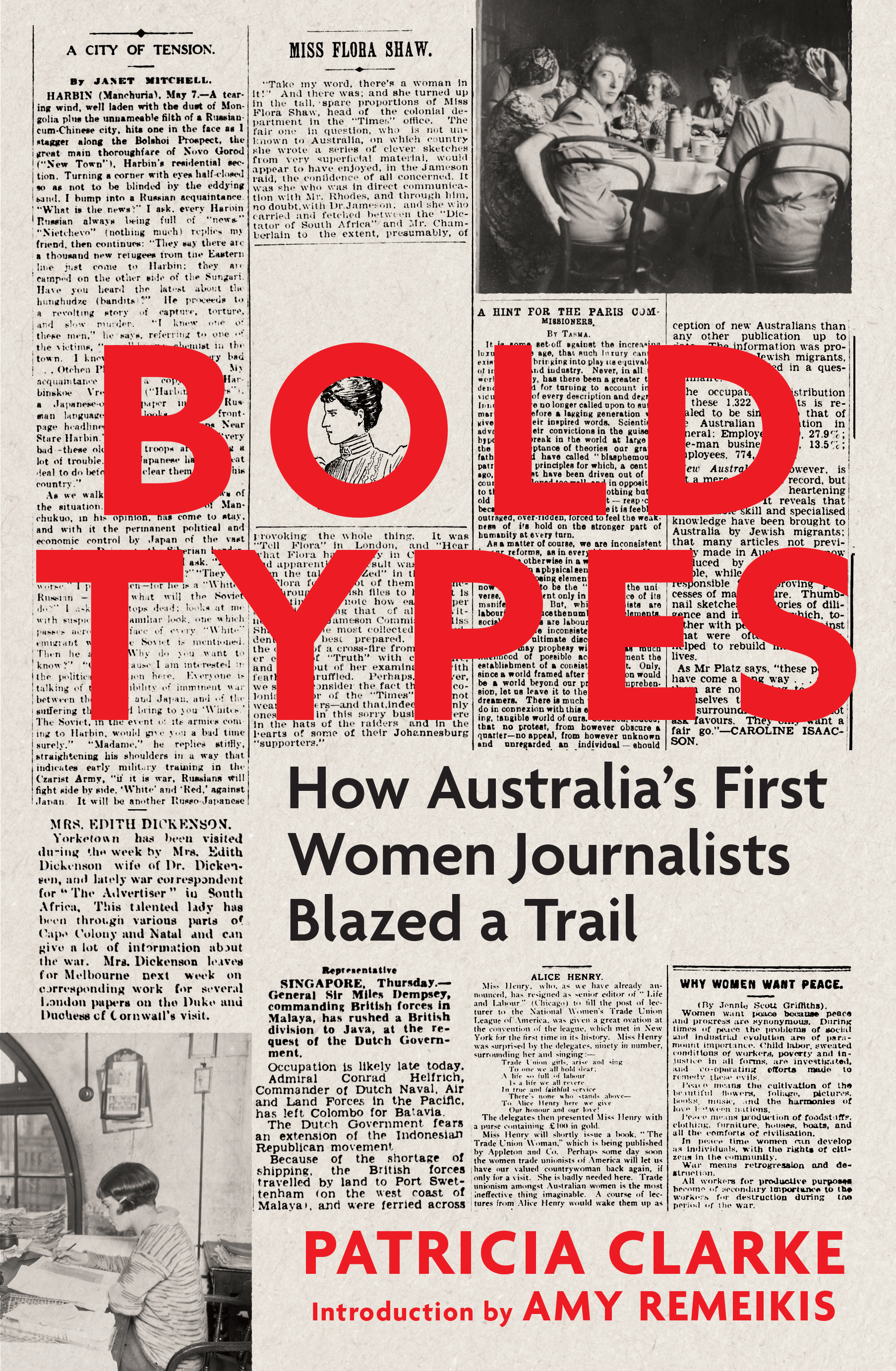

Bold Types

Bold Types tells the story of Australia’s first women journalists from 1860 to the end of World War II.

Tracing the journey of more than 13 independent, adventurous women who ventured far and wide and fought for relevance and gender equality, together these stories illustrate the gains and setbacks of women journalists over a century. In each successive story, their tenacious determination and courage shines through.

Bold Types author Patricia Clarke was a trailblazer herself, as the only woman on the Melbourne staff at the Australian News and Information Bureau in the early 1950s.