Cheney

Brew

National Library of Australia

The Prosecution Project is the kind of thing that couldn’t be imagined before the web and before Trove!

We began as a collaboration between a number of historians interested in exploring some questions about crime and the law in Australian history. Who was prosecuted, for what kinds of crimes, with what consequences, and what about the victims of crime - what were their stories?

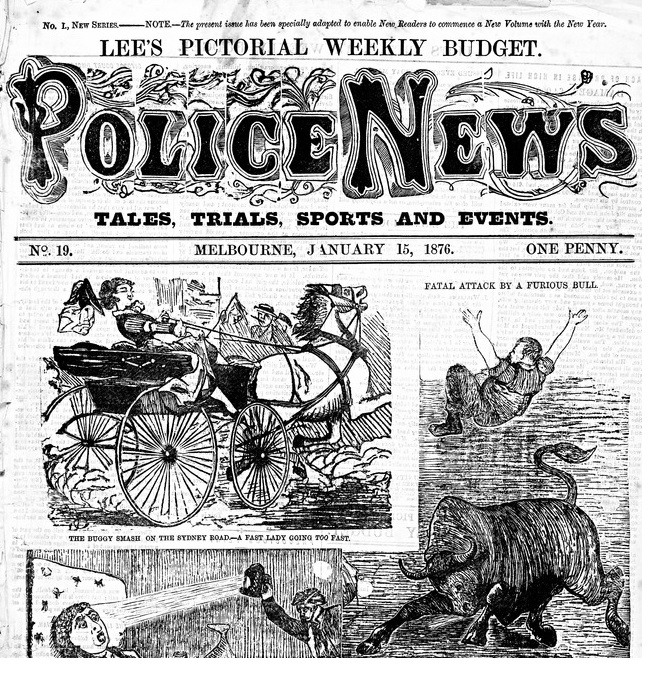

A lot of histories deal with these kinds of questions, but mostly at the level of individuals or select groups of people and at isolated or perhaps atypical points of time. We were interested in patterns, across Australia and over long periods of time. We were especially interested in the century ‘after the convicts’ from the gold rushes on.

We started with Supreme Courts, where the most serious offences were prosecuted, and which produced (for the most part) regular records of daily business in the kind of format that could be readily transcribed to be machine-readable. Our basic process involves transcription of court registers from digitised images of individual pages into a secure online database within a Griffith University server.

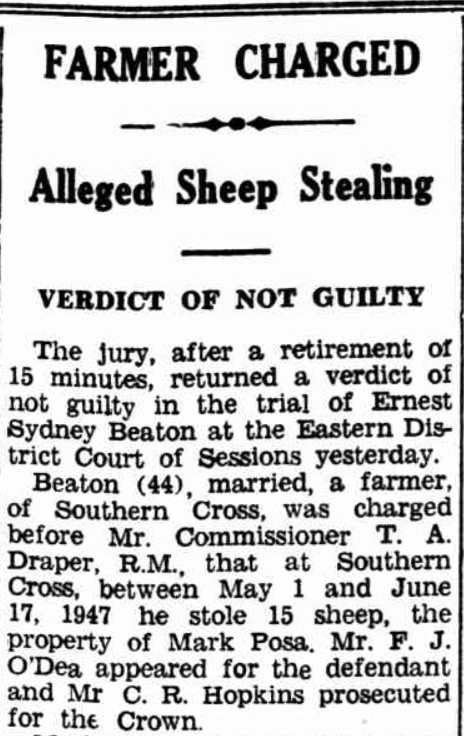

Original records in the court registers are limited in their detail. The enemy of understanding in history is the isolated fact. Without knowing where that fact sits in the world it belongs, we know nothing. For the kind of fact accessed by the Prosecution Project from court records, newspaper reports provide the context of the crime event and its aftermath. And so the Trove library of digitised newspapers is an indispensable tool for discovery of that wider world.

Our system was designed to be used by any number of users working at the one time and wherever they were located, as long as they had access to the internet. Early work was done by the research team alone – but after we wrote to all the family and local history societies in Australia we ended up recruiting a large number of volunteers. The volunteers have made an enormous contribution and continue to do so – for many their interest in cases they transcribe leads them direct to Trove where they can learn much more and in turn sometimes resolve ambiguities, such as the spelling of a name, often obscured in nineteenth century script.

From the beginning we imagined accessing newspaper reports through Trove as something we could do after entering our own data from the court archives. And that’s how we started the project. But the development of the Trove API that enabled machines to talk with each other was a step-change – with some deft work by our software engineer we were able to build into the very process of data entry a semi-automated search of the vast Trove library to see whether the person and date of the court event we were looking at had been reported in the newspapers of the time.

The API has enabled us to build a constantly increasing and rich set of data around individual crime events and court appearances that builds up a web of connections from that one point – telling us about crime victims and complainants, about arresting police and town magistrates, about trial judges and what they said at sentencing.

But that is not the end of the story of the Prosecution Project’s involvement with Trove. Continuing technology development and collaboration between data holders, such as libraries and archives, and data users, such as researchers and family historians means that Trove search has now become a way of accessing the Prosecution Project itself. A cycle of information retrieval allows those looking at Prosecution Project records to link directly to Trove items, or the reverse for those coming to their inquiries through Trove ‘People & Organisations’ records and perhaps not even knowing about the relevance of a past prosecution record to their family history.

For many users, Trove is primarily a newspaper library – but apart from pictures, maps and diaries, there are even more resources that investigations like the Prosecution Project can access. The addition of the NSW Police Gazette is a major addition – using the same methodologies of linking Trove addresses to Prosecution Project records we have been able to identify the missing information about offence or verdict in hundreds of New South Wales cases.

In this way we see Trove as a marvellous and intricate web, an information resource of many dimensions, linking disparate sources through well designed databases that prioritise accessibility, rewarding researchers and general users with an endless supply of possibilities for resolving questions and asking new ones.

Mark Finnane is the director of the Prosecution Project at Griffith University. https://prosecutionproject.griffith.edu.au/